News and Views

State Election Asks 2021

The State Election is fast approaching.

We have written to the ALP, Tasmanian Greens and Liberal Party with our election asks (enclosed) including:

- commit to building 10,000 public housing properties over the next decade; and

- repeal no reason end of lease evictions; and

- limit rent increases to CPI and/or a fixed percentage; and

- remove the ability to blacklist survivors of family violence; and

- introduce standard forms and lease agreements; and

- allow pets unless the landlord has a good reason for their exclusion;

- stronger regulation of short-term accommodation sector; and

- funding increase for services providing tenancy advocacy and enforcement.

Find the complete letter below:

Re: Commitment to Tenancy Reform at State Election

With the State Election less than one month away, we ask that consider adopting the following infrastructure spends, policy reforms and funding commitments as part of your election platform. In our opinion, your support for these reforms will provide better protections for the more than 50,000 Tasmanian households that rent.

We also enclose a Questionnaire which we ask be returned by Friday 23 April 2021. The results will be made publicly available on our website and on social media.

According to the most recent Australian Bureau of Statistics Census data, there was an 18 per cent increase in the number of residential tenants in Tasmania from 45,600 in 2006 to 51,000 in 2011 and over 54,000 in 2016.[1] Nevertheless, despite the increase in Tasmanians renting, housing for tenants is frequently of a poor quality, insecure and unaffordable. In our experience, many landlords ignore requests for repairs and maintenance and tenants are fearful to complain about their housing, because of the very real risk of a rent increase or eviction.

We believe these issues will only become more pronounced as a growing number of Tasmanians rely on the private rental market for their housing. We therefore seek your support for the following reforms, which will better protect tenants’ rights and ensure access to quality, stable and affordable housing for all.

- Safe, secure and affordable housing for all:

- Commit to building 10,000 public housing properties over the next decade

Housing in Tasmania has worsened since the last State Election in 2018 with more people in housing stress, more people waiting for social housing and more homeless. We urgently need increased supply of public housing to act as a break on skyrocketing rent increases and to ensure that everyone has a roof over their head. We endorse the recommendations of both Shelter Tasmania and the Tasmanian Council of Social Service that the State Government should commit to building 10,000 social housing properties over the next decade but strongly believe that the housing should be public not community housing.

- Security of Tenure

- Repeal no reason end of lease evictions

Adequate housing provides the foundation from which people can participate effectively in their community. As such, tenancy should be viewed as the provision of a basic human right rather than as a simple contractual arrangement for goods and services. Stability and certainty must be protected so that tenants are able to assert their rights without fear of eviction. However, this is not borne out in practice with a report published by CHOICE finding that around half of all renters worry they will be blacklisted from future tenancies and 14 per cent refuse to stand up for their rights because of the possibility of landlord recrimination.[2]

We strongly believe that principles of natural justice should inform the Residential Tenancy Act 1997 (Tas) (‘the Act’). If there is to be no change to the use of the property, tenants should be able to maintain their tenure unless there has been a proven breach of their residential tenancy agreement. We therefore recommend the repeal of those sections of the Act that allow a fixed-term lease to be ended purely on the basis of lease expiration.

- Rent Controls:

- Limit the amount of the rent increase to CPI and/or a fixed percentage.

- Rent increases to be set out at commencement of lease agreement.

Tasmania’s rent control laws are the weakest in Australia. Currently, the Act provides that a landlord can increase the rent as long as the last increase was at least twelve months prior and the tenant has been provided with 60 days’ notice. The only protection against excessive rent increases is a requirement that the Residential Tenancy Commissioner assess the increase against “the general level of rents for comparable residential premises in the locality” and “any other relevant matter”. With median rents across Tasmania having increased by 37 per cent over the last five years, a landlord can justify a rent increase of this amount for no other reason than that it is market rent. For example, in Southern Tasmania the median rent for a three-bedroom house has increased from $310 to $440 (42 per cent increase), in Northern Tasmania from $260 to $350 (34 per cent increase) and in North-west Tasmania from $250 to $300 (20 per cent increase).[3]

It is clear that market mechanisms are not working efficiently in the Tasmanian housing market. We strongly believe that rent increases occurring during a lease should be subject to controls as is the case in the Australian Capital Territory. In the ACT rent increases are limited to a rate based on inflation. The onus on contesting the rent increase is dependent upon the quantum. If the proposed increase is above the proscribed rate the owner has the onus of establishing that the increase is justified, and if below, the tenant must demonstrate that the increase is excessive.[4]

Additionally, the Act allows rent increases during a fixed-term lease agreement meaning that many tenants are required to pay a rent increase that they would not have signed up to if they had been made aware prior to signing the lease extension. We therefore recommend that landlords be required to inform tenants of the rent increase amount before requesting that they sign on to the lease extension.[5]

- Family Violence:

- Remove the ability to blacklist victims of family violence for damage or rental arrears caused by perpetrators

- Remove the liability of victims for the acts or omissions of perpetrators lawfully on the premises

Since the last State Election in 2018 the Act has been amended to allow survivors and perpetrators of family violence to terminate their residential tenancy agreement without penalty.[6] This is a welcome reform that is consistent with other Australian jurisdictions.[7] But more reform is needed to better protect survivors of family violence.

Currently, the Act allows landlords to keep a residential tenancy database (i.e. a blacklist) of tenants who have breached the terms of their lease agreement. Tenants can only be blacklisted for breaches that still require the repayment of monies (unpaid rent or damage to property) or for evictions from an immediate termination.[8]

In practice, this means that many family violence survivors continue to be punished for a perpetrator’s actions. If a survivor of family violence applies for a family violence order and the perpetrator is subsequently removed from the agreement, the survivor will often be required to pay all of the rent. This may lead to financial hardship and the risk that the survivor will fall into rental arrears. If the survivor is subsequently evicted due to rental arrears the landlord may blacklist the survivor making it difficult to find alternative accommodation. As well, where a survivor is evicted from their property due to the perpetrator’s ongoing damage of the property, or where damage has been done to the property by the perpetrator the landlord can have the survivor blacklisted.

We strongly recommend that Part 4C of the Act is amended to prohibit landlords and real estate agents from blacklisting tenants for actions arising from the actions of the perpetrator including damage to property and unpaid rent.

Finally, the Act provides that a tenant is liable for any act or omission of persons lawfully on the premises.[9] We strongly recommend that the automatic liability of tenants for the acts or omissions of others should be removed in circumstances where tenants can prove that the damage arose from family violence.[10]

- Standard Forms and Lease Agreements:

- Introduction of Standard Forms and Lease Agreements

Most lease agreements contain provisions that purport to exclude, restrict or modify the operation of the Act. A review by our lawyers of their files found a number of provisions contained in residential lease agreements that were inconsistent with the Act, including:

- That the tenant is responsible for the repair or replacement of whitegoods that came with the property; and

- That the tenant accepts the property in its current condition; and

- That the tenant must allow access to the property to carry out a valuation or appraisal; and

- That the tenant not cause a disturbance or annoyance to anyone else; and

- That the tenant must have the carpets cleaned by a professional cleaning company that has been approved by the landlord; and

- That the tenant is responsible for all costs associated with lodging a debt with a debt collection agency including the debt collectors costs.

The lack of standardisation means that many tenants believe that they are forced to comply despite the clause/s being unlawful under the Act. As well, tenants often raise their concern at the different forms used by landlords and real estate agents and the information contained therein. An excellent example is the application form provided to prospective tenants with a recent report finding that 60 per cent of renters surveyed believed that they were required to provide an excessive amount of information on the application form.[11]

A number of years ago we carried out a review of all real estate agencies who make their application forms publicly available and our investigation found that there is information requested of prospective tenants in some application forms that may be unlawful. There is also information required that we believe is discriminatory, amounts to an invasion of privacy or is simply unnecessary. Examples include:

- The requirement that prospective tenants provide a criminal history check; and/or a credit check; and

- The refusal of tenants who require Colony 47 financial assistance to pay the bond; and

- The refusal of any prospective tenant who has an outstanding debt; and

- The requirement that prospective tenants list their financial commitments; and

- The requirement that prospective tenants state their marital status; and

- The requirement that prospective tenants provide a minimum of four referees.

Much of this information is irrelevant to the tenancy or the ability of persons to maintain the tenancy successfully. Tenants who feel uncomfortable about providing information will often contact us requesting advice about their right to refuse. The lack of a standard application form means that there is practically very little that can be done. The tenant must provide the information required or face the very real risk that the application will be passed over in favour of someone who is prepared to provide the information.

We therefore strongly recommend that a standard residential lease agreement as well as standard forms, including a standard application form for all prospective tenants should be introduced.

- Pets:

- Allowed unless landlord has good reason for their exclusion

- Include ‘assistance animal’ in list of exceptions

The Act currently provides that a tenant is not allowed to have a pet without the landlord’s permission.[12] In practice, most lease agreements include a no pets clause meaning that the landlord does not have to give any thought to the tenant’s request. As a result, many tenants with pets are forced to look for rental accommodation in areas less accessible by public transport or to surrender their pet, with recently released Australian Housing and Urban Research Institute (AHURI) research finding 60 per cent of Australian households have a pet and about 15-25 per cent of surrenders are because their owner cannot find an accommodating rental property.[13] The same AHURI report also cited a study that found that property damage in households with pets was no more likely than damage without pets.[14]

We strongly believe that the Act should be amended so that all tenants have the ability to have a pet unless the landlord has reasonable grounds for their exclusion.[15] This is already the law in the Australian Capital Territory, Victoria and the Northern Territory.[16]

It should also be noted that the current exclusion of pets from rental properties does not apply to guide dogs.[17] In our opinion, this should be broadened to include ‘assistance animals’. This would make the Act consistent with the Anti-Discrimination Act 1998 (Tas) and the Disability Discrimination Act (Cth). The failure to expressly include ‘assistance animal’ has meant that we have had to institute legal proceedings on behalf of a number of tenants who have required such animals for their medical conditions.[18]

- Stronger regulation of short-term accommodation sector

- Entire properties that are not principal place of residence returned to long-term residential tenants

Airbnb and other short-term accommodation providers must be better regulated. Hundreds of private rental properties have been removed from long-term residential tenants across Hobart with a recent AHURI report finding that entire properties that are available to rent as short-term accommodation and available to rent for 60 days or more is equal to twelve percent of the entire private rental market in the Hobart City Council municipality; the highest rate in the country and one of the highest rates of any capital city anywhere in the world.[19] Unsurprisingly, the proliferation of short-term accommodation properties in the Hobart City Council municipality and throughout Tasmania has seen rents rise and supply dry up with the AHURI report concluding “even a modest reduction in Airbnb listings (about 17 per cent) is associated with a significant reduction in rents”.[20]

Entire properties should be banned from the short-term accommodation market to encourage owners to return those properties to long-term residential tenants. A more balanced policy would see homeowners able to rent out spare rooms in their own homes whilst returning entire properties to the private rental market.

- Tenant Advocacy:

- Funding increase for services providing tenancy advocacy and enforcement

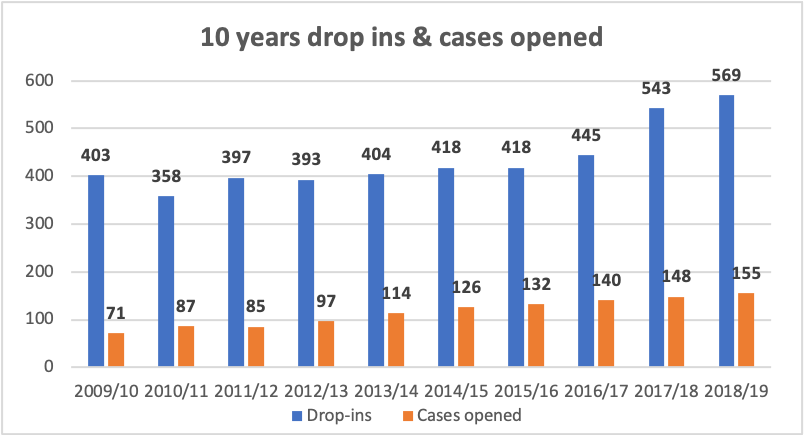

Current funding levels are not sufficient to meet the demand for our services. Our total recurrent funding of $310,000 per annum from both the State and Commonwealth has remained unchanged in real terms for many years despite the significant increase in demand for our services. For example, as noted earlier, the most recent Census data found that that there had been an 18 per cent increase in the number of residential tenants in Tasmania from 45,600 in 2006 to over 54,000 in 2016. And, as the following graph demonstrates, there has been a 41 per cent increase in the number of tenants seeking face-to-face legal advice from us and a doubling in the number of cases we have opened.

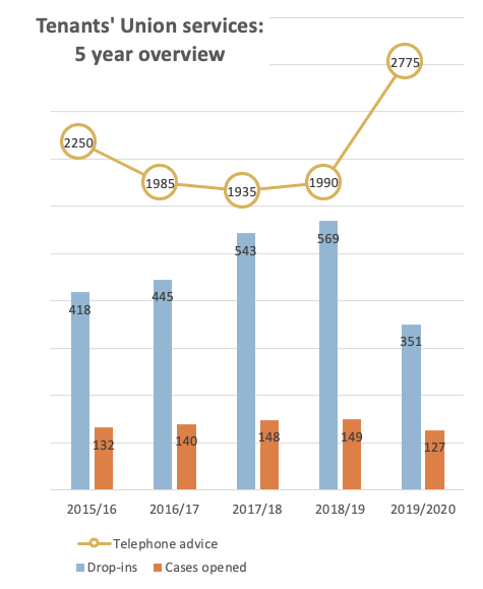

The onset of COVID-19 in March 2021 means that our data for the 2020-21 financial year cannot accurately be compared against previous years. Nevertheless, as the following graph highlights, the decrease in drop-ins and cases opened during 2020-21 was more than offset by the significant increase in telephone calls. Importantly, the data over the last five years demonstrates that the total number of clients has increased from 2800 in 2015-16 to 3253 in 2019/20, an increase of 16 per cent.

As well as increased demand for our service we are also concerned at the Department of Justice’s lack of regulatory enforcement with a recent Right to Information request confirming that between 2016/17 and 2019/20 the Residential Tenancy Commissioner determined that 365 complaints against landlords or agents for breaches of the Act were “well founded” but just seven resulted in a fine.

In summary, we hope that you will carefully consider adopting the infrastructure spends, policy reforms and funding commitments outlined above which in our opinion will provide increased protections to more than 50,000 households across Tasmania.

If you require any clarification or we can be of any further assistance please do not hesitate to contact us.

Yours faithfully,

Benedict Bartl

Principal Solicitor

Tenants’ Union of Tasmania

[1] Productivity Commission, Report on Government Services 2020, Tables 2A.25, 2A.26 and 2A.27.

[2] CHOICE, National Shelter and the National Association of Tenant Organisations, Unsettled: Life in Australia’s private rental market (February 2017). The report can be accessed at https://www.choice.com.au/money/property/renting/articles/choice-rental-market-report (accessed 12 April 2021).

[3] Tenants’ Union of Tasmania, Tasmanian Rents (September Quarter 2020). http://tutas.org.au/wp-content/uploads/2019/11/Tas-Rents-Sep-2020.pdf (accessed 12 April 2021).

[4] Section 68(3) of the Residential Tenancies Act 1997 (ACT) sets out the factors that are taken into account including: (a) the rental rate before the proposed increase; (b) outgoings or costs of the landlord in relation to the premises; (c) services provided by the landlord to the tenant; (d) the value of fixtures and goods supplied by the landlord as part of the tenancy; (e) the state of repair of the premises; (f) rental rates for comparable premises; (g) the value of any work performed or improvements carried out by the tenant with the lessor’s consent; and (h) any other matter the ACT Civil and Administrative Tribunal considers relevant.

[5] See, for example section 64A of the Residential Tenancies Act 1997 (ACT).

[6] Section 17 of the Family Violence Act 2004 (Tas).

[7] Section 102 of the Residential Tenancies Act 2010 (NSW). See also section 44 of the Residential Tenancies Act 1997 (ACT).

[8] Part 4C of the Residential Tenancy Act 1997 (Tas).

[9] Section 59 of the Residential Tenancy Act 1997 (Tas).

[10] This would bring Tasmania into line with other jurisdictions including section 233C of the Residential Tenancies Act 1997 (Vic) and section 89A(11) of the Residential Tenancies Act 1995 (SA).

[11] CHOICE, National Shelter and the National Association of Tenant Organisations, Unsettled: Life in Australia’s private rental market (February 2017) at 12. The report can be accessed at https://www.choice.com.au/money/property/renting/articles/choice-rental-market-report (accessed 12 April 2021).

[12] Section 64B of the Residential Tenancy Act 1997 (Tas).

[13] Australian Housing and Urban Research Institute, Housing and housing assistance pathways with companion animals: risks, costs, benefits and opportunities (AHURI Final Report No. 350 at 20). As found at at https://www.ahuri.edu.au/__data/assets/pdf_file/0026/66455/AHURI-Final-Report-350-Housing-and-housing-assistance-pathways-with-companion-animals.pdf (accessed 12 April 2021).

[14] Australian Housing and Urban Research Institute, Housing and housing assistance pathways with companion animals: risks, costs, benefits and opportunities (AHURI Final Report No. 350 at 32). As found at at https://www.ahuri.edu.au/__data/assets/pdf_file/0026/66455/AHURI-Final-Report-350-Housing-and-housing-assistance-pathways-with-companion-animals.pdf (accessed 12 April 2021).

[15] Examples could include council regulations that excluded backyard chickens or the rules of a body corporate.

[16] Sections 71AE and 71AF of the Residential Tenancies Act 1997 (ACT); Section 65A of the Residential Tenancies Act 1999 (NT); Division 5B of the Residential Tenancies Act 1997 (Vic).

[17] Section 64B(2) of the Residential Tenancy Act 1997 (Tas).

[18] As defined in section 9(2) of the Disability Discrimination Act (Cth). Examples include a dog trained to predict when its owner was likely to have an epileptic seizure and a pet bird who alleviated the side effects of its owner’s mental illness.

[19] Australian Housing and Urban Research Institute, ‘Marginal housing during COVID-19’ (AHURI Final Report No. 348). As found at https://www.ahuri.edu.au/__data/assets/pdf_file/0027/65970/AHURI-Final-Report-348-Marginal-housing-during-COVID-19.pdf).

[20] Australian Housing and Urban Research Institute, ‘Marginal housing during COVID-19’ (AHURI Final Report No. 348). As found at https://www.ahuri.edu.au/__data/assets/pdf_file/0027/65970/AHURI-Final-Report-348-Marginal-housing-during-COVID-19.pdf (accessed 12 April 2021).

The results of the questionnaire will be published next Friday.